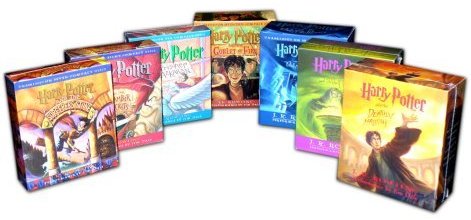

This week Jenni and I finished re-listening to Jim Dale’s masterful reading of the Harry Potter series.

We enjoyed it so much the first time that we read the books again two years later, and the timing was just right. We loved it right out of the gate in book 1. We made so many more thematic connections the second time through that we missed the first time. (We initially focused on putting together the broad storyline.) What a pleasure.

We can relate to what Alan Jacobs writes about here—at least with reference to Harry Potter and Narnia—in The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011):

We can relate to what Alan Jacobs writes about here—at least with reference to Harry Potter and Narnia—in The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011):

Children often have this experience:

- the Harry Potter saga has wrapped up,

- the Anne of Green Gables tales are done.

Neil Gaiman, that gifted writer of fantasies for children and adults, gave a talk a few years ago in which he described the centrality of C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books to his early life:

“I remember what I did on my seventh birthday—I lay on my bed and I read the books all through, from first to the last. For the next four or five years I continued to read them. I would read other books, of course, but in my heart I knew that I read them only because there wasn’t an infinite number of Narnia books to read.”

It’s no wonder

- that writers besiege C. S. Lewis’s estate seeking permission to write further Narnian adventures,

- or that responsibility for Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys hash been passed on to several generations of authors, who will continue to invent new mysteries for the young sleuths to unravel probably until the world’s end.

But adults can feel the same grief:

- how many thousands of readers have never been able to reconcile themselves to the fact that Jane Austen wrote only six novels? Thus the recent sequels to Pride and Prejudice—even, in a perverse way, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies—and the attempts by various authors to complete the novels Austen was working on when she died.

- A similar speculative eagerness surrounds Dickens’s unfinished Mystery of Edward Drood: Why did Dickens have to die at fifty-eight? Surely, he had not only this novel but half-a-dozen more in him!

So we turn again and again to our favorites, striving to calculate how best to maintain the magic.

- I have had several conversations with my son over the years at moments when he was undecided whether his last encounter with the Harry Potter books had receded sufficiently in his memory that a successful rereading was possible.

- And success in such endeavors is a doubtful thing: there is always the possibility, devotees know all too well, that too many rereadings squeezed into too narrow a time frame will drain the books’ power and leave them forever inert on the shelves. And this would be lamentable.

- (Lately I have been asking myself whether I have sufficiently forgotten the details of Patrick O’Brian’s novels of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars that I can return to them with vibrant pleasure. I hover over those memories like a cook over a stewpot: in another year, I think, the books and I will be ready.)

(pp. 34–35, formatting added)

Related:

I have much the same experience when rereading the Bible. Perhaps God endowed us with this particular bent for that particular purpose?